The 'Good' Wehrmacht

The Myth of Innocence in Post War Germany

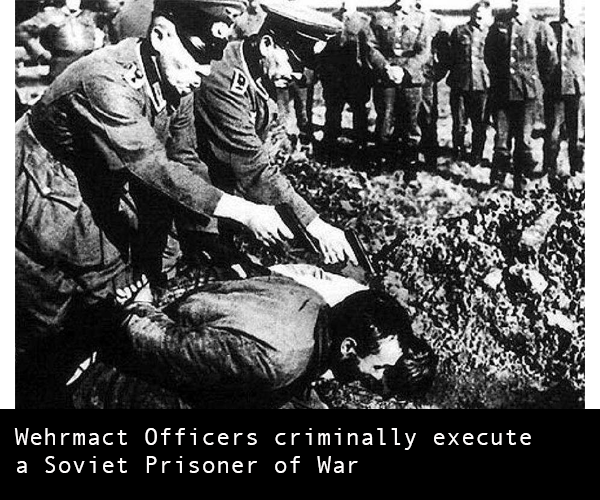

Warning! This post describes war crimes committed by German forces in the Second World War, and contains graphic images. May not be suitable for all readers.

Germany committed terrible crimes during the Second World War. This is not in doubt. However, in the years immediately after the end of the war, there was much debate, both inside West Germany and in the West, as to who exactly committed these crimes. There was a trend to attribute the crimes to Nazis and term Germans as victims. Specifically, there was a concerted effort by the Post War West German government and people as a whole to attribute all crimes of Hitler’s regime to the Schutzstaffel (SS) and the Nazis, leaving the German armed forces (the Wehrmacht) innocent of any crimes. This trend eventually became known as the myth of the ‘Good’ or ‘Clean’ Wehrmacht. This is of course completely false. The Wehrmacht was a willing and constant participant in German war crimes.

“The Wehrmacht is not just an institution, […] but in a significantly more diffuse sense, as enterprise, status-organization, terror unit, a part of the population. ‘Crimes of the Wehrmacht’ are in so many words crimes of everyman, crimes of everyman’s husband, father, brother, uncle, grandfather.” 1

“As in Eastern Europe, the idea of a ‘clean Wehrmacht’ in the Netherlands would prove more myth than reality.“ 2

Despite the evidence against it, the myth was a constant presence in post war West Germany. The myth of the ‘Good’ Wehrmacht was a changing political issue over time. First it was the mechanism of establishing Germany in the world. Later it would become another part of Germany’s national shame. The myth was used by the governments of Konrad Adenauer and his successors to establish the place of West Germany in the world, that being a willing, independent and equal ally against Soviet aggression. The myth of the ‘Good’ Wehrmacht gave West Germany a place to build off of. Later governments would also attempt to use the myth to further their own political aims, but would soon realize that the myth had become a controversy for a new generation. To examine this changing political issue, two specific case studies will be presented. The first comes from the early years of West Germany, and follows the establishment of the West German army in the early 1950s, and the domestic and international ramifications. The second is the tale of the Bitburg controversy, which helps to expose how the myth of the ‘Good’ Wehrmacht became a sensitive issue to German national pride and identity regarding the recent past.

OLD ENEMIES MADE FRIENDS: ADENAUER, THE WEST, AND THE NEW ARMY

The Myth of the ‘Good’ Wehrmacht was not isolated inside of Germany. As much as the myth was used as a tool to rebuild German national identity following the catastrophe of the Second World War, the myth was also used to great effect in the matter of foreign policy. The myth helped to facilitate West German rearmament and the newfound place for West Germany in the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO). Initially, Germany was punished after the war. Thousands of officials and soldiers of the old regime were interned, and a campaign of denazification was begun.

“[T]op MG [Military Government] officials repeatedly vowed to denazify their jurisdiction in Germany thoroughly” 3

However, within a few years, West Germany was essential to the NATO strategy to defend against a possible Soviet attack along the Iron Curtain. Due to this, “the once vigorous denazification campaign stopped and a joint American/German production of remembering commenced that fostered a myth of the German Wehrmacht and its behaviour in WWII.”4 The rehabilitation of the Wehrmacht and the rise of the myth was a direct precondition of West German rearmament after the war. This was specified by the Himmerode Memorandum of 1950. This report was compiled by a group of former Wehrmacht officers called into conference by Konrad Adenauer, the first Chancellor of West Germany.5 These officers viewed that “a German army could be called into existence only after representatives of the Western powers had issued a formal declaration rehabilitating the soldiers of the Wehrmacht.”6 These officers were of course acting in their own self interest, among their number they included Hermann Foertsch, who was “one of the leaders responsible for indoctrinating the troops with National Socialist ideas.”7

Others present at the Himmerode Conference would go on to posts of power in the Bundeswehr (the new West German army), such as Hans Speidel and Adolf Heusinger. This underscores the simple fact of West German rearmament. On one hand the modern Bundeswehr does not view itself as a successor agency to the Wehrmacht or the earlier Reichswehr (the army of the Weimar Republic), and makes stringent efforts to distance itself from the crimes of the past.8 On the other hand there is the issue that the new Bundeswehr needed an experienced officer corps to be able to stand up to any Soviet aggression. Of course, these officers would have to be drawn from the cadre of former Wehrmacht officers.

A political problem now arose. Adenauer’s government could not in any respect be seen as publicly accepting former Nazi officers, one time persecutors, into a military that’s entire mission was the defence of the German people.9 A solution was quickly found in separating the terms Nazi and Wehrmacht. This was done by persuading American supreme commander Dwight D. Eisenhower to retract earlier comments where he “identified it [the Wehrmacht] with National Socialism.”10 He would later tell domestic German reporters that “a real difference existed between German soldiers and officers as such and Hitler and his criminal gang.”10 Adenauer would also make statements in the Bundestag (West German parliament) which “officially restored the honour of those soldiers ‘who had not been guilty of any offence.’”10 Thus a distinction had been drawn between the Nazi criminals and the soldiers of the Wehrmacht.

These statements, and accompanying legislation in the West German Basic Law 11 allowed for former Wehrmacht officers and soldiers to reclaim pensions and positions previously lost to denazification efforts. This was not it’s greatest possible effect though. The head of the West German government and the most powerful officer of the Allied powers had explicitly endorsed the myth of the ‘good’ Wehrmacht, providing the myth with a powerful legitimatizing force in West Germany.

Officer wearing medals from all three eras of 20th Century Germany From antiquephotos.com

Officer wearing medals from all three eras of 20th Century Germany From antiquephotos.com

The myth did not only need to be legitimatized inside of Germany though. The Western Allied powers, who barely ten years before had been hellbent on the destruction of the entire German regime, Wehrmacht included, now needed to provide reasoning as to why former Nazi officers were being put into positions of power again. The myth of the ‘Good’ Wehrmacht was spread around the Allied powers and enshrined in propaganda. Daniel Clayton covers this extensively in his paper They Were Soldiers Just Like Us. A principal example which Clayton uses was a picture book printed in 1950, called Life’s Picture History.12 The book principally gave the American’s more credit for ending the war in Europe than the Soviets, and made very little mention of the “war of extermination on the Eastern Front.”12 It also made light of atrocities committed by the Germans, attributing them to “Nazis and not German solders per se.”13 The book would go on to describe the victims of German atrocities as people “Hitler didn’t like.”13 The terminology here is extremely important. Not only did the book refuse to identify any crimes as being committed by the Germans, but it also placed the blame squarely, and only, at Hitler’s feet. 13 The book created the message it wished to send, that the crimes of the Nazis were not the crimes of the Germans, through omission. By omitting any mention of the Wehrmacht, the Wehrmacht could not be implicated in any crimes, and was thus innocent. This book, thoroughly popular in the United States,12 would help “foster the myth of the ‘Clean’ [‘Good’] Wehrmacht in American popular memory.”14

This shift of terminology away from German crimes and towards Nazi crimes had an explicit political purpose. In American Cold War planning, “West Germans became indispensable allies and the front-line troops in the most dangerous war ever.”14 For the Americans to explicitly condemn the prior actions of the very soldiers that it relied on was a political impossibility. No German would fight for the new world order led by the United States if the United States simultaneously condemned their entire nation as a nation of criminals. Therefore the United States was forced to accept, whether willingly or unwillingly, the shift of blame from Wehrmacht to Nazi as a result of the political climate of the time. In trying to present a united front for NATO against Soviet aggression, the United States was forced to forget about animosities of the past and prepare for the future. The Cold War, while never heating up, still made strange bedfellows.

A GROWING ISSUE: THE BITBURG CONTROVERSY

The myth of the ‘Good’ Wehrmacht did not die in the era of Adenauer. In the 1980’s, the myth would become the centre of a complex political argument regarding West Germany’s place in the world. This argument came to light during American President Ronald Reagan’s visit to Germany in 1985. Reagan, and West German Chancellor Helmut Kohl visited Bergen Belsen concentration camp and a military cemetery near the town of Bitburg.15 Kohl would stated during the visit to the cemetery that “Bitburg can be regarded as a symbol of reconciliation and of German - American friendship”16 while Reagan “remembered the German soldiers as victims, too, of Hitler’s regime.”17 It appears to Hannah Holtschneider, the author of German Protestants Remember the Holocaust, that this visit with Reagan was meant to evoke similar sentiments that Kohl’s visit with French President François Mitterrand at Verdun did in 1984.18 Kohl and Mitterrand had “held hands in silence”, and were “intending symbolically to show their mutual respect and readiness to forgive past wrongs.”18 In Holtschneider’s view, if there had been a similar positive reaction to the Bitburg visit as there had been to this, Kohl would have fulfilled “his ambition to draw a line under Germany’s NS [National Socialist] past and to establish West Germany as a fully recognized and trusted member of the Western Alliance.”18 This supposed plan backfired unfortunately. Unbeknownst to Kohl, the cemetery at Bitburg contained the graves of Waffen-SS troops.17 This event was highly criticized, but the political fallout was contained by West German President Richard von Weizsäcker’s speech on the fortieth anniversary of Germany’s surrender on May 8, 1945.19 It has been posited by Micheal Prince in War and German Memory that Bitburg had a far greater effect than the political scandal for Kohl’s government. Prince asserted that “honouring German soldiers at such a place as Bitburg symbolically equated the war dead of both sides, despite the fact that the two had fought for diametrically opposing causes and principles.”20 In Prince’s view, “Germany sought to undercut the judgements of existing cultural memory and replace them with a softer, more palatable and palliative narrative in which all suffering is alike and all dead equal victims of war.”20

From German History in Documents and Images

From German History in Documents and Images

Just as the government of Konrad Adenauer had tried to brand German war crimes as crimes of the Nazis and Hitler, Kohl can be seen as trying to do the same thing. He came at it from a different angle. He did not directly attempt to exonerate all Germans through pinning their crimes upon the actions of a fanatical few. Rather he sought to paint all Germans, which of course included the ordinary men of theWehrmacht, as victims of the Nazis. This was in effect an exoneration of all Germans in the same vein as Adenauer. While Kohl did not name the perpetrators, it is clear they could not have been true Germans nor the men of the Wehrmacht, for they were the victims. Just like Adenauer, Kohl attempted to change the terminology of the narrative, from perpetrator to victim, just as Adenauer changed Wehrmacht to Nazi. Kohl’s attempted message here is not surprising. The controversy it caused is far more significant, as touched upon below.

THE COST?

The main difference between Kohl’s actions and Adenauer’s was the reaction to them. Adenauer was the first chancellor of West Germany, while Kohl was the last (he would later lead a united Germany into the late 1990’s). This change in time reflected an immense change in the perception of the myth of the ‘Good’ Wehrmacht in West Germany. That Kohl met with any controversy for his statements at all is indicative of the willingness of a new generation of Germans to accept and attempt to learn from their grandparent’s crimes, rather than try to forget the painful past. The myth of the ‘Good’ Wehrmacht had become a changing political issue. No longer was it the main method for achieving a place for Germany in the post war new world order. Rather it became a controversy, and hopefully it will eventually become another painful memory in Germany’s painful past.

While this examination has focused almost inclusively on the German effects of the myth of the ‘Good’ Wehrmacht, there is also the question of how the rest of the world interpreted the myth. Earlier, the initial American retelling of the war in Life’s Picture History, can be seen as taking a supportive view of the myth of the ‘Good’ Wehrmacht. Interestingly, there remains to this day a clear memory of the myth in American popular culture. Take for example the HBO television series Band of Brothers. In a memorable scene of the show (embedded below), a captured Wehrmacht general gives a speech to his troops one last time before entering captivity at the hands of the show’s central characters. At 1:19 into the video, he tells his troops that they “ have fought bravely and proudly for [their] country.”21 These are hardly the words one would expect if the show writers were aware of the terrible crimes of the Wehrmacht. The show’s main characters express sympathy and identify with the Wehrmacht general’s words. Band of Brothers, while a drama, was produced as a window into the lives and thoughts of ordinary soldiers. Thus the writers must believe that the ordinary American soldier at the time made a distinction between the honour of the Wehrmacht and the crimes of the Nazis. The myth has found it’s way into the American popular consciousness. This popular consciousness may do more for Germany’s international image then an entire generation of German Chancellor’s speeches, for it speaks to the way that the actions of Germany’s past are perceived outside of Germany.

It is perhaps in this that the lasting impact of the myth of the ‘Good’ Wehrmacht can be seen most easily. The myth still pervades modern life, and has evolved past a political message. For some, the myth is another way to remember the Third Reich, as it gives a way to acknowledge the events of the past while providing a silver lining. The myth of the ‘Good’ Wehrmacht is escapism at it’s core, an attempt to escape painful memories and move on to a hopefully more bright future. One would hope that this was the aim of Konrad Adenauer, Helmut Kohl and other members of the West German governments of the Cold War, that they had a true wish for reconciliation and remembrance. The alternative assumption is that Adenauer, Kohl and others wished to belittle the crimes of the Germans as the crimes of the few out of some malice and a wish to forget about the crimes of the past. This alternative is perhaps to much of a truth to bear, that history is being erased before it can even be properly told. In a world of ‘fake news’ and far right populism, it is more important than ever to address the past as it actually happened, and to not attempt and appease sentiments or pre-existing beliefs in the telling of history.

Botel, Frank. “Firm lines of Tradition.” German Federal Ministry of Defence. Accessed March 27, 2017. https://www.bmvg.de/portal/a/bmvg/start/sicherheitspolitik/bundeswehr/geschichte/traditionslinien

Clayton, Daniel M. “They were soldiers, just like us …” War, Literature & The Arts 25, no. 1 (2013)

“Basic Law for the Federal Republic of Germany” Deutscher Bundestag. Accessed March 27, 2017. https://www.bundestag.de/blob/284870/ce0d03414872b427e57fccb703634dcd/basic_law-data.pdf

Foray, Jennifer. “The ‘Clean Wehrmacht’ in the German-Occupied Netherlands, 1940-5” Journal of Contemporary History 45, no.4 (2010): 768-787

Holtschneider, K. Hannah. German Protestants Remember the Holocaust: Theology and the Construction of Collective Memory. Münster, Germany: Lit, 2001.

Levy, Alexandra F.. “Promoting Democracy and Denazification: American Policymaking and German Public Opinion.” Diplomacy & Statecraft 26 no.4 (2015): 614-635

Prince, K. Michael. War and German Memory: Excavating the Significance of the Second World War on German Cultural Consciousness. Toronto: Lexington Books, 2009.

Rosenhaft, Eve. “Facing Up to the Past ‐ again?” Debatte: Journal of Contemporary Central and Eastern Europe 5, no. 1 (1997): 105-118.

Shafir, Shlomo. “Constantly Disturbing the German Conscience: The Impact of American Jewry,” in Remembering the Holocaust in Germany 1945 - 2000, ed. Dan Michman, 120-141. New York: Peter Lang, 2002.

Spielberg, Steven & Hanks, Tom. Band of Brothers: Points. Television. Home Box Office, 2001. From https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VcMk85ZsBh0

Wette, Wolfram. The Wehrmacht: History, Myth, Reality. Cambridge, US: Harvard University Press, 2007

-

Eve Rosenhaft, “Facing Up to the Past ‐ again?,” Journal of Contemporary Central and Eastern Europe 5, no. 1 (1997): 106. ↩

-

Jennifer Foray, “The ‘Clean Wehrmacht’ in the German-Occupied Netherlands, 1940-5.,” Journal of Contemporary History 45, no. 4 (2010): 768 ↩

-

Alexandra Levy, “Promoting Democracy and Denazification: American Policymaking and German Public Opinion.” Diplomacy & Statecraft 26 no.4 (2015): 615 ↩

-

Daniel Clayton, “They were soldiers, just like us …” War, Literature & The Arts 25, no. 1 (2013): 3 ↩

-

Wolfram Wette, The Wehrmacht: History, Myth, Reality. (Cambridge, US: Harvard University Press, 2007), 236 ↩

-

Ibid., 236 - 237 ↩

-

Ibid., 236 ↩

-

Frank Botel, “Firm lines of Tradition.” German Federal Ministry of Defence. Accessed March 27 2017. https://www.bmvg.de/portal/a/bmvg/start/sicherheitspolitik/bundeswehr/geschichte/traditionslinien ↩

-

The ceremonial oath of the Bundeswehr: “I pledge to serve the Federal Republic of Germany loyally and to defend the right and the freedom of the German people bravely” ↩

-

Wolfram Wette, The Wehrmacht: History, Myth, Reality. (Cambridge, US: Harvard University Press, 2007), 237 ↩ ↩2 ↩3

-

Article 131 accorded pensions to former civil servants and Wehrmacht officers — “Basic Law for the Federal Republic of Germany” Deutscher Bundestag. Accessed March 27 2017. https://www.bundestag.de/blob/284870/ce0d03414872b427e57fccb703634dcd/basic_law-data.pdf ↩

-

Daniel Clayton, “They were soldiers, just like us …” War, Literature & The Arts 25, no. 1 (2013): 5 ↩ ↩2 ↩3

-

Hannah Holtschneider, German Protestants Remember the Holocaust: Theology and the Construction of Collective Memory (Münster, Germany: Lit, 2001), 77 ↩

-

Ibid. p. 77 (see footnote 85) ↩

-

Daniel Clayton, “They were soldiers, just like us …” War, Literature & The Arts 25, no. 1 (2013): 9 ↩ ↩2

-

Hannah Holtschneider, German Protestants Remember the Holocaust: Theology and the Construction of Collective Memory (Münster, Germany: Lit, 2001), 78 ↩ ↩2 ↩3

-

Shlomo Shafir, “Constantly Disturbing the German Conscience: The Impact of American Jewry,” in Remembering the Holocaust in Germany 1945 - 2000, ed. Dan Michman, (New York: Peter Lang, 2002), 130 ↩

-

Michael Prince, War and German Memory: Excavating the Significance of the Second World War on German Cultural Consciousness (Toronto: Lexington Books, 2009), 47 ↩ ↩2

-

Steven Spielberg & Tom Hanks. Band of Brothers: Points. (Home Box Office, 2001). 1:19 - 1:23 ↩