The Lethargic Admiralty

Nelson, Trafalgar, and Reform in the Royal Navy 1815-1860

At the conclusion of the Napoleonic Wars, Britain’s Royal Navy emerged as the most powerful military force in the world. Britain’s position as a superpower in the nineteenth century would be maintained by the size, power, and fighting spirit of her navy. At first glance, British victory in the Napoleonic Wars would seem to ensure British dominance for the remainder of the century. However, the reverence paid by those in power to the memory of Nelson, Trafalgar and the Napoleonic Wars would be directly responsible for the stagnation of the Royal Navy in the nineteenth century.

Nelson’s memory was put to greate use in the Great War © National Army Museum

Nelson’s memory was put to greate use in the Great War © National Army Museum

The Royal Navy of the mid nineteenth century, while a formidable force, was more of a force on paper than an effective fighting force. The stagnation of the Royal Navy due to the memory of Nelson, Trafalgar and the Napoleonic Wars can be seen through two lenses. The first is the slow pace of organizational reform in the Royal Navy, specifically in relation to the navy’s arcane system of promotion for senior officers, and lack of mandatory retirement. The Royal Navy would continue to be organized under traditional lines until mid-century, casting doubts on the ability of the Royal Navy’s officer corps to fight a war had the need arisen. The navy’s slow organization reform also had the additional effect of leaving men in command who were not ready for the effects the Industrial Revolution would have on the Royal Navy. The transition to steam would see the Royal Navy’s technical innovation stagnate and many of the innovations of naval technology in the nineteenth century would be French, not British.

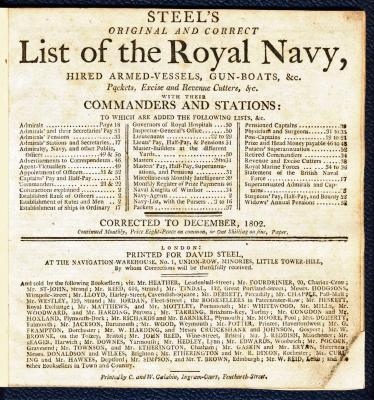

In the period between 1815 and the Crimean War, Nelson and Trafalgar loomed heavily in the minds of both the civilian administrators and senior officers of the Admiralty, the British government ministry in charge of the navy. Officers who served in the Napoleonic Wars would continue to serve for many years, and under the system of the time, would only be promoted past the rank of captain by seniority, rather than any notion of ability.1 2 An officer who had made it to the rank of captain would steadily move up the seniority list as those above him died, his relative position never changing.3 Other than death or court martial, there was no way off the seniority list.4 The only way one could become an admiral, and command a fleet, was to reach the top of the list of captains and enter the list of admirals, where promotion proceeded under the same system.5 Some men who had served as captains for very short periods of time during the Napoleonic Wars would die as the highest ranking admirals in the latter half of the century.6

This system may seem obviously wrong to us now, but this was not so clear at the time. The problem of promotion only became an issue when there was a long period of peace,7 as there was after 1815. During the Napoleonic Wars huge numbers of officers had been promoted,8 to meet Britain’s wartime needs, but there would not be another major war for many years. After the Napoleonic Wars, the British fleet was reduced to a shadow of its wartime footprint, and there was huge unemployment among commissioned officers.9 The large number of old officers who held seniority created little room for new officers to move up in the smaller peacetime navy. While the Royal Navy still admitted adequate numbers of junior officers, the glut of officers at the top of the list slowed down promotion for all.10 11 Men would wait decades for promotion.

The Navy List from 1802, the document which recorded every officer’s place in the seniority system Jane Austen Society of North America

The Navy List from 1802, the document which recorded every officer’s place in the seniority system Jane Austen Society of North America

In 1840, “the first hundred captains [had] held that rank about 30 years.”12 Those officers who had been made Post Captain during the Napoleonic Wars were reluctant to allow any changes to this system, thereby imperilling the ability of the Royal Navy to change in the fast moving nineteenth century. When mandatory retirement (i.e. removing old officers from the active list so younger men could advance) was being debated in the House of Commons, Parliamentary Secretary to the Admiralty Lord Clarence Paget stated that mandatory retirement “would hurt the feelings” of “old and valuable officers who served their country during those wars in which it gained its greatest glory.”13 Rear Admiral Griffiths, himself a beneficiary of this system, argued in front of a Royal Commission in the House of Lords that mandatory retirement would be “a breach of engagement, harsh and unjust in its exercise, producing immense painful distress to those who may be so treated.”14 At issue was that it was a point of pride for naval officers in this era to remain on the active list.15 Retirement was an explicit acknowledgement that they would never go to sea again, and it was only beneficial to the Admiralty to get rid of them, not to the officers themselves.16 17 It is hard to not sympathize with these officers. While many were from the upper class, and could “revert to the social life of [their] class on shore,”18 many more were not, and having been brought up in the navy from a young age, did not seek other employment, remaining “singularly faithful” to the Admiralty,19 forever hoping for a new posting from a navy that did not have enough jobs to give out.20 These men, having no prospects of a career at sea, did not have much left to them other than the pride in the service they had done in Britain’s time of need.

Sympathy aside, the glut of officers in the aftermath of the Napoleonic Wars created the the ugly legacy of the Royal Navy’s finest hour. Having a bunch of old men past their glory days as admirals was not a recipe for success when it came to fighting wars. If there had been a major war amongst the Great Powers in this era, the Royal Navy’s ability to fight may have been in jeopardy simply for lack of qualified leaders. In the Crimean War, there would be incidents showing that a navy under the command of old men could not be truly effective.21 Stanley Bonnett, in the Price of Admiralty, makes mention of (among others) one Admiral Napier, who ordered his men to sharpen their cutlasses in preparation for the war.22 Given the success the Light Brigade had with sabres against Russian cannons in the very same war, this was perhaps not the best advice.

Portrait of Admiral Charles Napier. Attributed to John Simpson - Palácio Nacional de Queluz, Public Domain

Portrait of Admiral Charles Napier. Attributed to John Simpson - Palácio Nacional de Queluz, Public Domain

It was not easy to replace these old warriors with younger, abler officers either. In wartime, commanders would be drawn from the available admirals. Having been promoted purely based on seniority, most men on the admirals list were older Napoleonic warriors, far past the age where they could lead a fleet at sea effectively.23 In the Politics Of Naval Supremacy, Gerald S. Graham quotes a Vice Admiral Bowles, who in 1852 stated that “there was ‘scarcely an officer now fit for service’” who could command a fleet.24 This problem also trickled down to the lower ranks of the navy. As there were not many seagoing posts in the small peacetime navy, few junior officers had experience at sea, and officers would often request transfers when ordered to sea, as they doubted their ability to handle a large ship at sea.25 Had the Royal Navy put in a system of retirement for senior officers sooner, and reformed the idiotic seniority lists, junior officers would have been able to more easily move up the ladder of promotions in the navy, gain more experience, and been more equipped to fight wars when called upon. If the Admiralty had earlier instituted a formal system of retirement for officers too old to go to sea, the Royal Navy would have been much better off. Instead it catered to the whims of Nelson’s Band of Brothers in the early part of the nineteenth century, to potentially disastrous effect.

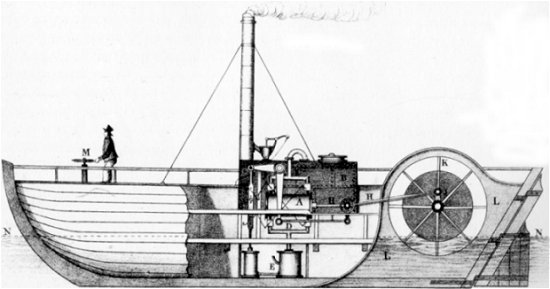

Leaving the older officers of the Napoleonic Wars in place had another chilling effect that worked in parallel with the stagnation of promotion to dull the Royal Navy’s effectiveness. Much like one’s 98 year old grandmother in this day and age, these old warriors in charge were very resistant to adopting new technology. In the early portion of the century Britain had a commanding lead in industry over any other European power, and the Royal Navy should have been able to take advantage. In 1800 there were thirty two steam engines in Manchester alone.26 Steam engines for ships first started appearing in the early 19th century, with the Charlotte Dundas (the first steam boat) sailing in 1802.27 28

Charlotte Dundas cut-away drawing by Robert Bowie. Public Domain

Charlotte Dundas cut-away drawing by Robert Bowie. Public Domain

Though used by civilians for several years, and by the navy in tug boats since the early 1820s,29 the Royal Navy would not put steam engines into their battleships until mid century, and only then because the French had started doing so first.30 Steam power was only one of several innovations which the British got to second, with the French being the first to adopt the use of shells in naval gunnery in 1827,31 and the first to commission an ironclad warship with La Gloire in 1859.32 Each of these was an inexcusable lapse which could have cost the Royal Navy dearly. The British Isles were the birthplace of the Industrial Revolution, yet the Royal Navy allowed itself to fall behind in the application of these revolutionary new technologies. Britain, which in 1815 was virtually unchallenged on the high seas, was now playing catch up by mid-century. The Royal Navy remained the preeminent power throughout the period,33 and the British response to Gloire, the Warrior, “was the most revolutionary [ship] in the history of naval architecture,”34 but no matter the response, in this period the Royal Navy was not the first to innovate.

HMS Warrior, the first fully ironclad warship. By geni - Photo by User:Geni, CC BY-SA 4.0

HMS Warrior, the first fully ironclad warship. By geni - Photo by User:Geni, CC BY-SA 4.0

The blame for this lies squarely at the feet of the navy’s aging leaders, who repeatedly refused the offers of engineers who wished to interest the Admiralty in their inventions, such as John Ericsson, one of several inventors who independently developed the screw propellor.35 The Royal Navy’s leaders had a general a lack of willpower, and harboured antipathy towards steam power and other innovations of the Industrial Revolution. In the Price of Admiralty, Stanley Bonnett writes that “with few notable exceptions the men who fought alongside Nelson or who sent Nelson and his men to fight lacked a grasp of what machinery could do for ships.”36 Bonnett continues to say that “instead of finding out what the new machines could do for warships the Admiralty policy was to ignore it all.”37 The resistance to steam among the Royal Navy’s leaders, by and large veterans of the Napoleonic Wars, cannot be overstated. The First Lord of the Admiralty, Lord Melville, would say in 1828 “‘that the introduction of steam is calculated to strike a fatal blow to the the naval supremacy of the Empire.’”38 For the British, there was not “any overriding motive for making naval changes.”39 In their view, the wooden sailing ships of the Royal Navy “which had served them so long and so well,” did not need improvement.40 The leaders of the Royal Navy did not want their world to change, and they only allowed the Royal Navy to modernize when it was required for the survival of British preeminence, in the face of French innovation and public outcry over the threat of invasion.41 The technology which had won Trafalgar and the Napoleonic Wars would never win another war, but the leaders of the Royal Navy could not see this until it was staring them straight in the face.

Oil painting of Robert Dundas, Lord Melville, seated in an armchair. By Colvin Smith (1795–1875), Public Domain

Oil painting of Robert Dundas, Lord Melville, seated in an armchair. By Colvin Smith (1795–1875), Public Domain

Had there been younger, or even just more open minded, men at the head of the Royal Navy, development of the naval applications of the fruits of the Industrial Revolution may have happened far sooner. Whether this would have had any effect on the history of Europe during the long nineteenth century is unclear. There was of course no general European war with which to test the theory that Britain through this time period was a paper tiger, powerful in theory yet set to crumble when push came to shove. What is sure is that with other nations competing with Britain’s industry and Britain’s navy, “the age of Pax Britannica was over.”42 Had the Royal Navy had a more equitable system of promotion earlier in the century, or at least a retirement plan, younger officers who were not relics of the Napoleonic Wars may have led the service, and perhaps the Royal Navy would have innovated sooner, and not been subject to the same challenges, overstated expectations, and arms races which would plague the Royal Navy in the waning days of the nineteenth century and the lead up to the First World War.

Beeler, John. ’Fit For Service Abroad’: Promotion, Retirement And Royal Navy Officers, 1830–1890, The Mariner’s Mirror, 81:3, 300-312, 1995

Bonnett, Stanley. The Price of Admiralty: an indictment of the Royal Navy 1805-1966. London: Hale, 1968

Graham, Gerald Sandford. The Politics of Naval Supremacy: studies in British maritime ascendancy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1965

Lewis, Michael. “Armed Forces And The Art Of War: Navies.” Chapter in The New Cambridge Modern History, edited by J. P. T. Bury, 10:274–301. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1960.

Lewis, Michael. The Navy in Transition, 1814-1864; a social history. London: Hodder and Stoughton, 1965

Lloyd, Christopher. A Short History of the Royal Navy: 1805 to 1918. London: Routledge, 2016.

Royal Commission on Naval and Military Promotion and Retirement. Report of commissioners for inquiring into naval and military promotion and retirement: with appendices. 235 XXII.1. London: Her Majesty’s Stationery Office, 1840

-

Stanley Bonnett. The Price of Admiralty: an indictment of the Royal Navy 1805-1966 (London: Hale, 1968), 120 ↩

-

Michael Lewis. The Navy in Transition, 1814-1864; a social history (London: Hodder and Stoughton, 1965), 51 ↩

-

Lewis, The Navy in Transition, 50-51 ↩

-

Lewis, The Navy in Transition, 51 ↩

-

Lewis, The Navy in Transition, 51 ↩

-

Lewis, The Navy in Transition, 53 ↩

-

Lewis, The Navy in Transition, 59 ↩

-

Bonnet. The Price of Admiralty, 120 ↩

-

Lewis, The Navy in Transition, 48 ↩

-

Lewis, The Navy in Transition, 70 ↩

-

Lewis, The Navy in Transition, 70 ↩

-

Royal Commission on Naval and Military Promotion and Retirement. Report of commissioners for inquiring into naval and military promotion and retirement: with appendices 235 XXII.1 (London: HMSO, 1840), 243. Testimony of Captain J.W.D. Dundas, RN ↩

-

John Beeler. ’Fit For Service Abroad’: Promotion, Retirement And Royal Navy Officers, 1830–1890, (The Mariner’s Mirror, 81:3, 300-312, 1995), 306 ↩

-

Royal Commission on Naval and Military Promotion and Retirement. Report of commissioners for inquiring into naval and military promotion and retirement, 241. Testimony of Rear Admiral A.J. Griffiths RN ↩

-

Lewis, The Navy in Transition, 80 ↩

-

Lewis, The Navy in Transition, 76 ↩

-

Lewis, The Navy in Transition, 6 ↩

-

Lewis, The Navy in Transition, 81 ↩

-

Lewis, The Navy in Transition, 81 ↩

-

Lewis, The Navy in Transition, 81 ↩

-

Bonnet. The Price of Admiralty, 121. ↩

-

Bonnet. The Price of Admiralty, 121 ↩

-

Lewis, The Navy in Transition, 74 ↩

-

Gerald S. Graham. The Politics of Naval Supremacy: studies in British maritime ascendancy. (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1965), 106 ↩

-

Bonnet. The Price of Admiralty, 54 ↩

-

Bonnet. The Price of Admiralty, 26 ↩

-

Bonnet. The Price of Admiralty, 26 ↩

-

Bonnet. The Price of Admiralty, 52 ↩

-

Lewis, The Navy in Transition, 194 ↩

-

Michael Lewis. “Armed Forces And The Art Of War: Navies” chapter in The New Cambridge Modern History (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1960), 278 ↩

-

Bonnet. The Price of Admiralty, 58. The adoption of shells for naval guns had huge consequences, as a wooden ship could now be blown apart by an explosive shell. In the Price of Admiralty, Stanley Bonnett ponders that if there had been a decisive naval battle against the French in 1827, British command of the sea “could have ended in little more than twenty-two years [since Trafalgar]” (Bonnet. The Price of Admiralty, 60) ↩

-

Christopher Lloyd. A Short History of the Royal Navy: 1805 to 1918 (London: Routledge, 2016), 58 ↩

-

Lewis. “Armed Forces And The Art Of War: Navies,” 274 ↩

-

Lloyd. A Short History of the Royal Navy, 59. The specific’s of Warrior’s design is not terribly important for these purposes, but she was revolutionary in that “she was not just another wooden ship cut down [a wooden ship clad in iron], but an iron hulled ship which was larger, faster and stronger than her French rival.” (Lloyd. A Short History of the Royal Navy, 59). Warrior is also remarkable in that she survives to this day in Portsmouth as a museum ship ↩

-

Bonnet. The Price of Admiralty, 67 - 68. Ericsson would go on to develop the United States Navy’s first warship driven by a propellor, the Princeton, in 1843 (Bonnet. The Price of Admiralty, 70), and later the equally revolutionary Monitor during the American Civil War ↩

-

Bonnet. The Price of Admiralty, 26 ↩

-

Bonnet. The Price of Admiralty, 26 ↩

-

Bonnet. The Price of Admiralty, 51 ↩

-

Lewis. “Armed Forces And The Art Of War: Navies,” 275 ↩

-

Lewis. “Armed Forces And The Art Of War: Navies,” 275 ↩

-

Lloyd. A Short History of the Royal Navy, 59 ↩

-

Graham. The Politics of Naval Supremacy, 121 ↩